American Minute with Bill Federer

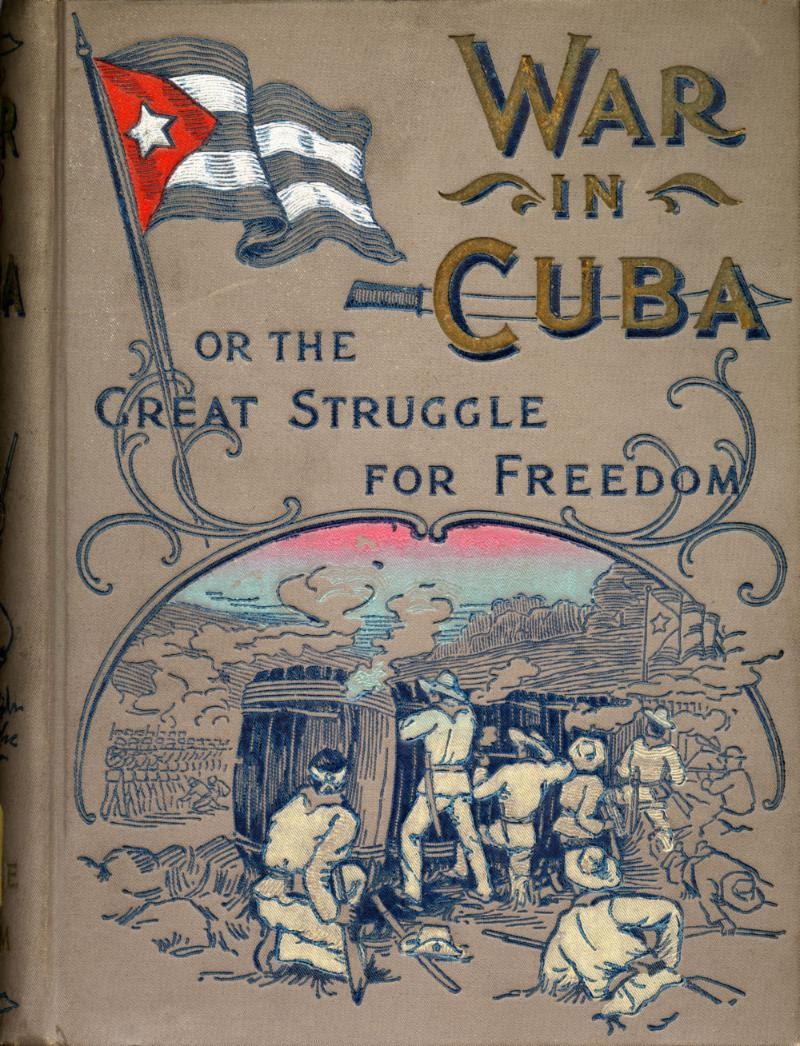

Cuba’s struggle for freedom from slavery

|

|

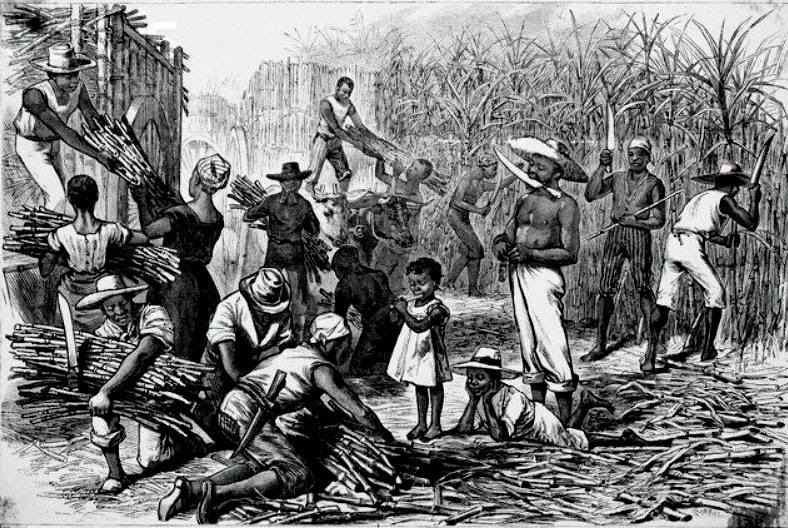

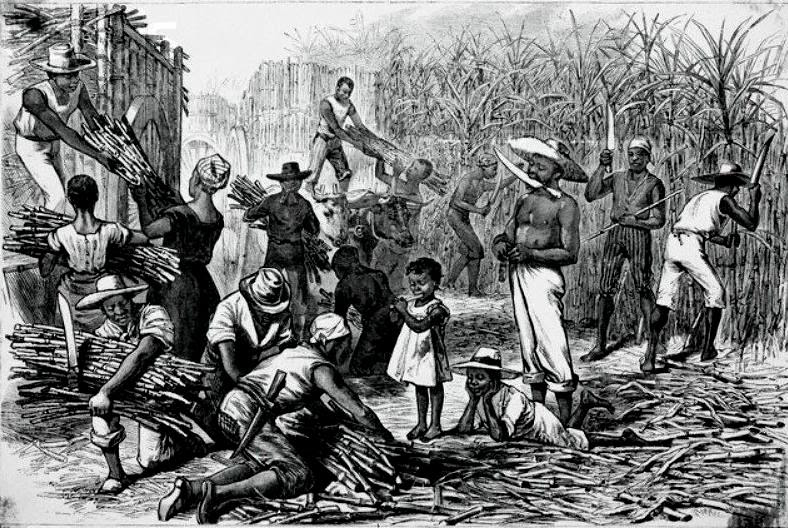

Slavery began in Caribbean in the 1500s, predominantly for working on sugar plantations.

Many slaves were native American in the 16th century, brought in from Ireland in the 17the century, or purchased in enormous numbers from Muslim slave markets in Africa in the 18th and 19th centuries.

On Haiti, slaves revolted against French control in 1792, and in 1807, the U.S. and Britainoutlawed the importation of slaves, but slavery continued in Cuba.

|

|

President James Buchanan wrote December 19, 1859:

“When a market for African slaves shall no longer be furnished in Cuba … Christianity and civilization may gradually penetrate the existing gloom.”

|

|

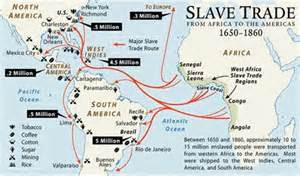

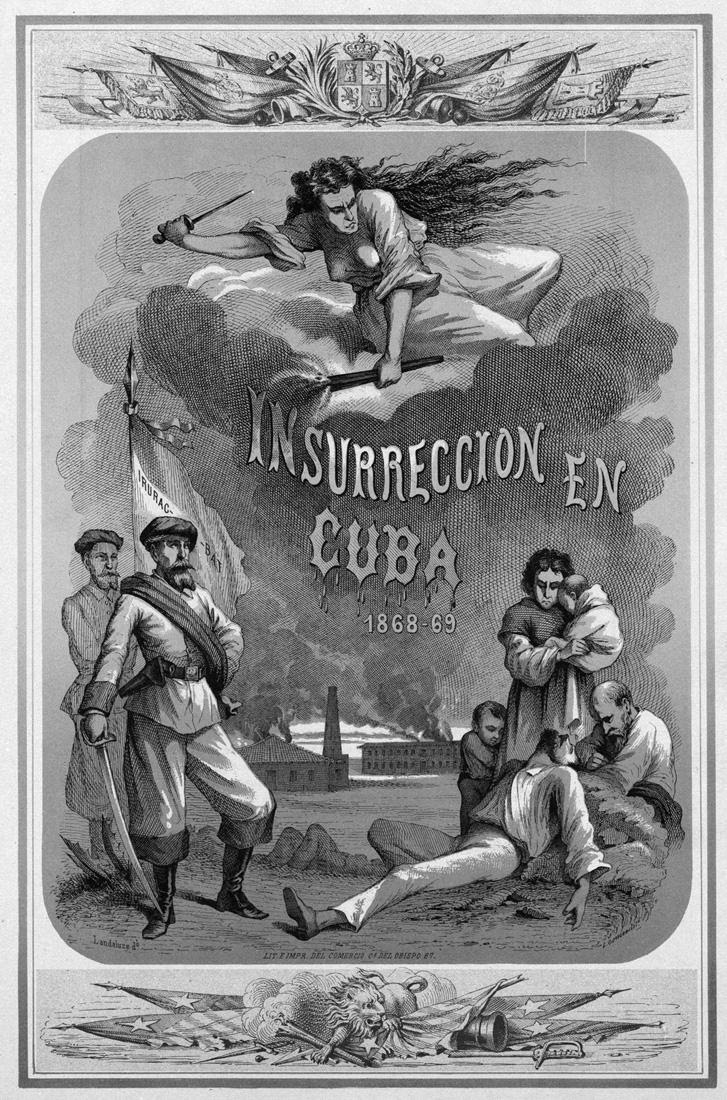

In 1868, a revolt was begun by a wealthy Cuban sugar farmer named Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, called Padre de la Patria (Father of the Country).

|

|

Céspedes freed his slaves and began Cuba’s first war for independence — the Ten Years War — against the oppressive government of Spain. He stated:

“Citizens: that sun you can now see raising above the Turquino Peak has come to illuminate the first day of Cuba’s freedom and independence.”

Freed slaves joined together with criollos — those of Spanish ancestry born in Cuba — to fight for freedom and to end slavery.

|

|

Similar to America”s Declaration of Independence, Céspedes was one of the signers of the “10th of October Manifesto,” 1868, a translation of which reads:

“When rebelling … against … Spanish tyranny we want to indicate to the world the reasons for our resolution.

Spain governs us with iron and blood;

-it imposes … taxes at will;

-it (takes from) us … all political, civil and religious freedom;

-it has put us under military watch in days of peace … (and they) catch, exile and execute without …. any proceedings or laws;

-it prohibits (us from) freely assembling, (unless) under the (presence) of military leaders; and

-it declares (as) rebels (those who want) remedy for so many evils …”

|

|

The Manifesto continued:

“Spain loads us with hungry employees who live from our patrimony and consume the product of ours work.

So that we do not know our rights, it maintains us in … ignorance; and so that we do not learn to exert it, it keeps us away from the administration of … public thing(s) …

It forces us to maintain an expensive … army, whose unique use is to repress and to humiliate us.

Its system of customs is so perverse that we (would have) already perished … (had it not been for) the fertility of our ground …

It prevents us (from) writing … and it (hinders) intellectual progress …

It has promised to improve our condition, and … it has deceived … us, and it (has) left us (only an) appeal to the arms to defend our properties, to protect our lives and to save our honor.

To the God of our consciousness we appeal, and to the good faith of the civilized nations …”

|

|

The 10th of October Manifesto concluded:

“We aspire to (have) popular sovereignty and … universal suffrage.

We want to enjoy the freedom for whose use God created the man.

We profess sincerely the dogma of … brotherhood … tolerance and justice, and consider all men, equal, and … not be excluded from its benefits; nor even the Spaniards, if they decide to live peacefully among us.

We want … (to) take part in the formation of the laws, and in the distribution and investment of the contributions.

We want to abolish … slavery and compensate whoever is harmed.

We want freedom of meeting, freedom of the press and freedom of … conscience, and

We request … respect (of) the inalienable rights of … man, (the) foundation of … independence and the greatness of (our) towns.

We want to remove from the yoke of Spain and to become a free and independent nation.

If Spain recognizes our rights, (it) will have in Cuba an affectionate daughter; if it persists in subjugating … us, we are resolute to die before (we will) be under his domination.”

|

|

President Ulysses S. Grant stated December 2, 1872:

“Slavery in Cuba is … a terrible evil … It is greatly to be hoped that … Spain will voluntarily adopt … emancipation … in sympathy with the other powers of the Christian and civilized world.”

|

|

President Grant said December 1, 1873:

“Several thousand persons illegally held as slaves in Cuba … The slaveholders of Havana … are vainly striving to stay the march of ideas which has terminated slavery in Christendom, Cuba only excepted.”

|

|

In 1878, the Spanish Government crushed the revolt, ending “The Ten Years War” in which over 200,000 died.

Another “Little War” took place in 1879.

Under international pressure, Spain ended slavery by Royal decree in 1886.

|

|

In 1895, open rebellion against Spain broke out in Cuba.

|

|

Spain sent Governor Valeriano Weyler to smash freedom-loving Cubans.

|

|

Weyler rounded up nearly 300,000 Cubans and forced them into crowded concentration camps.

|

|

This policy may have been copied from the Democrat-controlled U.S. Congress which passed the 1830 Indian Removal Act, authorizing Federal troops to force Cherokee Indians into FEMA-style camps before marching them to Oklahoma.

|

|

Concentration camps were expanded during America’s Civil War, where 215,000 Southerners were held — 26,000 dying in captivity; and 195,000 Northerners held — 30,000 dying in captivity, such as in the Andersonville Camp.

|

|

Britain, during the Second Boer War, 1899-1902, forced both White and Black South Africans into concentration camps.

|

|

This policy evolved into:

- Imperial Japan’ concentration camps for Filipinos and others;

- Hitler’s National Socialist Workers Party camps for Jews and others;

- Pol Pot’s Communist Khmer Rouge torture camp & “killing fields”;

- Chinese and North Korean labor camps; and

- Stalin’s Union of Soviet Socialist Republics “gulag” camps.

|

|

In Cuba, between 1896-1897, nearly a third of country’s population was in concentration camps.

With cesspools of raw sewage, 225,000 died of starvation, exposure, dysentery, and diseases, like yellow fever.

|

|

Pleas for help reached the United States to intervene.

|

|

In 1898, the U.S.S. Maine was in Havana’s Harbor and it blew up under suspicious circumstances on February 15, beginning the Spanish-American War.

|

|

On April 20, 1898, Congress wrote:

“The abhorrent conditions which have existed for more than three years in the Island of Cuba, so near our own borders, have shocked the moral sense of the people of the United States, have been a disgrace to Christian civilization …

Resolved … the people of the Island of Cuba are, and of right ought to be, free.”

|

|

On May 1, Commodore Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay.

|

|

On July 3, the United States, aided by Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, captured Santiago, Cuba, and the war soon ended with Cuba’s independence from Spain.

|

|

On July 6, 1898, President William McKinley wrote:

“With the nation’s thanks let there be mingled … prayers that our gallant sons may be shielded from harm … on the battlefield and in the clash of fleets …

while they are striving to uphold their country’s honor …”

|

|

The Treaty officially ending the Spanish-American War was signed DECEMBER 10, 1898.

|

|

President McKinley wrote:

“At a time … of the … glorious achievements of the naval and military arms … at Santiago de Cuba,

it is fitting that we should pause and … reverently bow before the throne of divine grace and give devout praise to God, who holdeth the nations in the hollow of His Hands.”

|

|

Many wanted Cuba to be under the authority of the United States, similar to Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Hawaii or Panama.

|

|

Not wanting to be imperialistic, America instead recognized Cuba’s independence on May 20, 1902, though it maintained a naval base at Guantanamo Bay.

|

|

In 1902, Estrada Palma became Cuba’s first President.

Unfortunately, soon after, in 1905, a revolt occurred against Palma.

Liberals burned down government buildings.

After an attempted assassination, liberal leader José Miguel Gómez fled to New York City demanding U.S. intervention:

“The United States has a direct responsibility concerning what is going on in Cuba … and is under the duty of putting an end to this situation.”

|

|

In September of 1906, Cuban President Palma sent an urgent plea for help to President Theodore Roosevelt, who sent to Cuba the U.S. Secretary of War William Howard Taft.

|

|

When Estrada resigned, Roosevelt appointed Taft as Provisional Governor of Cuba.

Many Cubans petitioned to have their country become part of the United States.

Taft’s replacement, Charles Magoon, allowed seeds of racial division to grow, as the Havana Post wrote in 1909: “His work here … caused two blades of grass to grow where but one had grown before.”

|

|

In 1908, José Miguel Gómez was elected President.

|

|

At the same time, an Independent Party of Color was founded which increased division among Cubans along racial lines for decades to come, resulting in demonstrations, riots and rebellion.

|

|

Gómez crushed the race rebellion in 1912, with such force that it alienated most blacks from political involvement.

Corruption grew under Gómez, with his government using the news media to push his controlling agenda.

|

|

In 1924, a new candidate arose, Gerardo Machado, who was so popular that he was the Presidential candidate for all three of the major political parties. He was unopposed in his reelection to a second term.

|

|

Machado brought honesty, stability, and foreign investment, such as American hotels, restaurants and tourism.

Condition continued to improve until the 1929 Stock Market Crash and the Great Depression.

Collapsing sugar prices led to protests which forced President Machado into exile.

|

|

In the 1920s, communists also began infiltrating student groups at the University of Havana, and formed the Cuban Communist Party.

|

|

In 1933, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada, son of the 1868 Padre de la Patria (Father of the Country), briefly became Cuba’s president for one month.

|

|

His hopes were dashed with he was forced out by Sergeant Fulgencio Batista and the Democrat Socialist Coalition.

|

|

Batista ruled Cuba 1940 to 1944, when Ramon Grau San Martin won the election, followed by Carlos PrÃo Socarrás in 1948.

In 1952, Batista and his new Progressive Action Party staged a coup and retook power, outlawing communists.

|

|

At the time, two-thirds of Cubans had the highest standard of living in Latin America, with tourism, baseball, and casinos, but the remaining third suffered with unemployment or was in dire rural poverty.

|

|

In 1956, Fidel Castro started a rebellion.

Batista responded with more arrests, imprisonments, and executions.

Senator John F. Kennedy stated October 6, 1960:

“Batista murdered 20,000 Cubans in seven years … and he turned Democratic Cuba into a complete police state – destroying every individual liberty.”

|

|

Castro was hailed as a rising leader, even being invited to speak at Harvard University.

In 1959, Castro forced Batista to flee.

|

|

Though he had promised freedom, once in power, Castro quickly set up a communist dictatorship, seizing thousands of acres of farmland from Cuban citizens and arrested anti-revolutionaries.

|

|

An observable pattern in history is, that whenever a tyrannical government is overthrown, unless citizens have been trained in Judeo-Christian principles of self-government, the country quickly succumbs to internal chaos, out of which another tyrannical dictator seizes power.

Castro imprisoned and enslaved dissidents, and made agreements with the Soviets.

|

|

One of Castro’s key men was Che Guevara, who stated:

“We executed many people by firing squad without knowing if they were fully guilty. At times, the revolution cannot be stop to conduct much investigation …

|

|

Hatred as an element of the struggle … transforming him into an effective, violent, selective, and cold killing machine.

Our soldiers must be thus; a people without hatred cannot vanquish a brutal enemy …

I’d like to confess … I discovered that I really like killing.”

|

|

Thousands of citizens, including church leaders, were tortured and executed.

|

|

By some estimates, over 100,000 were ruthlessly killed.

|

|

During Castro’s reign, over 1.5 million Cubans fled to the United States.

Castro died November 25, 2016.

|

|

In hopes of a new era, the United States reopened its Embassy in Havana, Cuba, on July 20, 2015.

|

|

American Minute is a registered trademark of William J. Federer. Permission is granted to forward, reprint, or duplicate, with acknowledgment.

|

|

Schedule Bill Federer for informative interviews & captivating PowerPoint presentations: 314-502-8924 wjfederer@gmail.com

|

|

Miracles in American History CTVN

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

American Minute with Bill Federer Presidents on Jewish Persecution & Israel

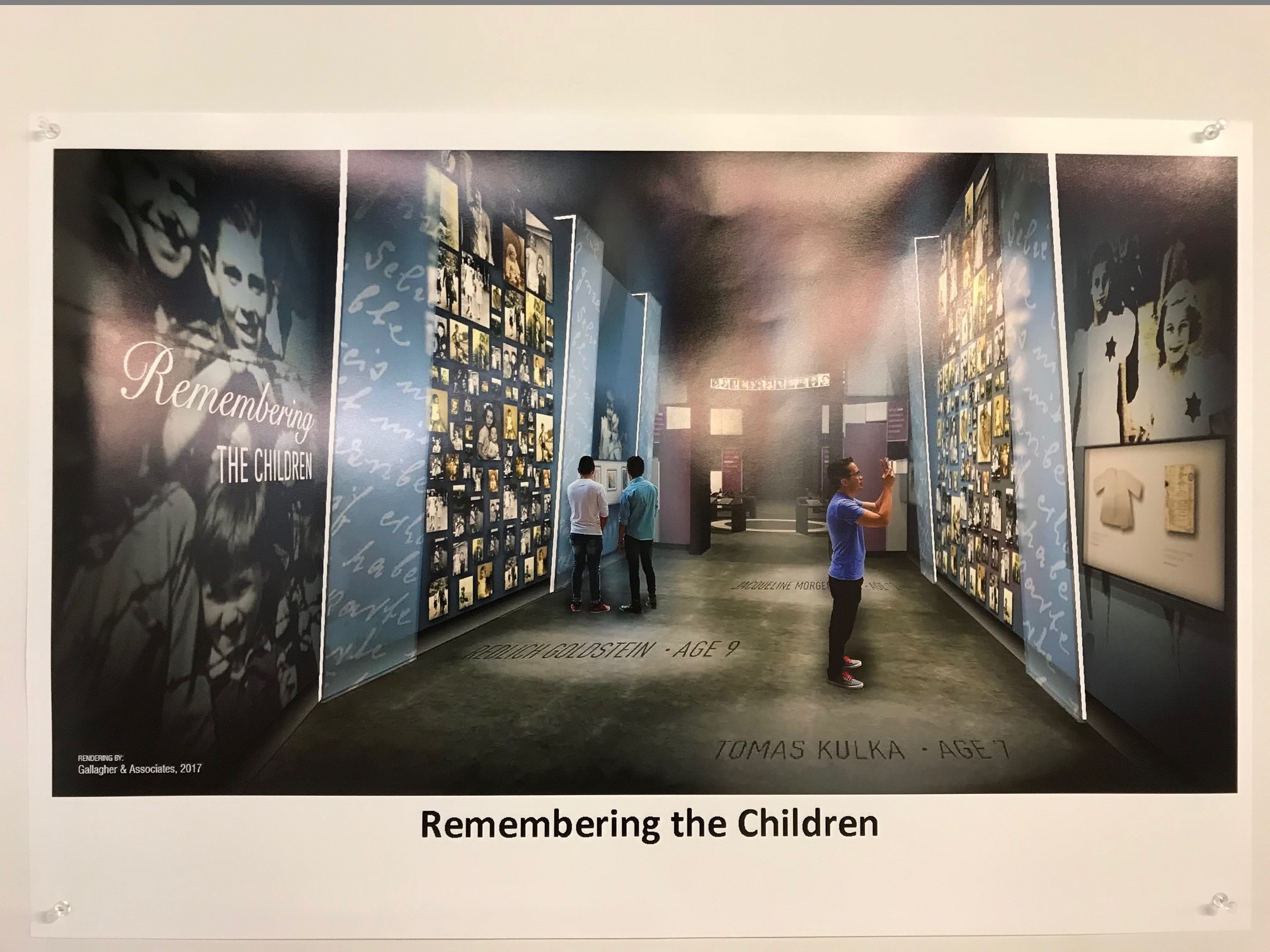

American Minute with Bill Federer Presidents on Jewish Persecution & Israel The HOLOCAUST: What Some Textbooks No Longer Teach

The HOLOCAUST: What Some Textbooks No Longer Teach