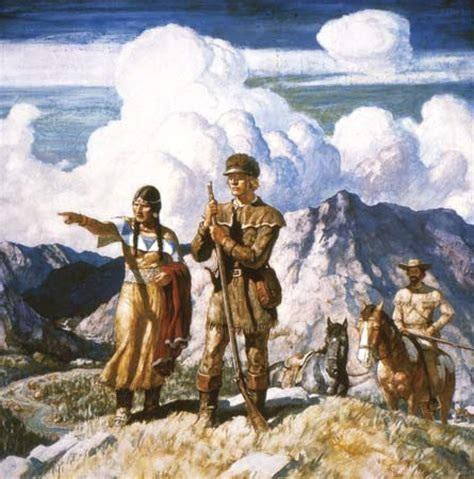

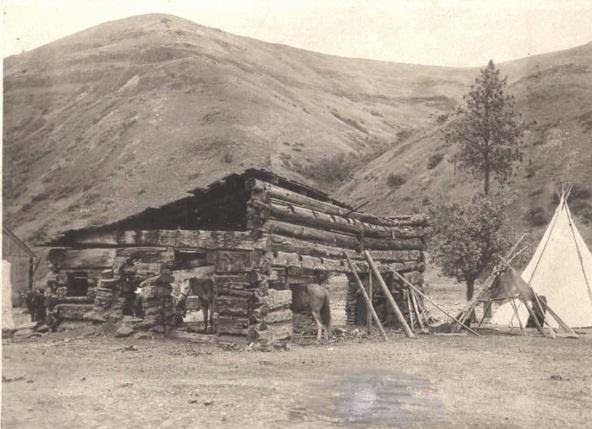

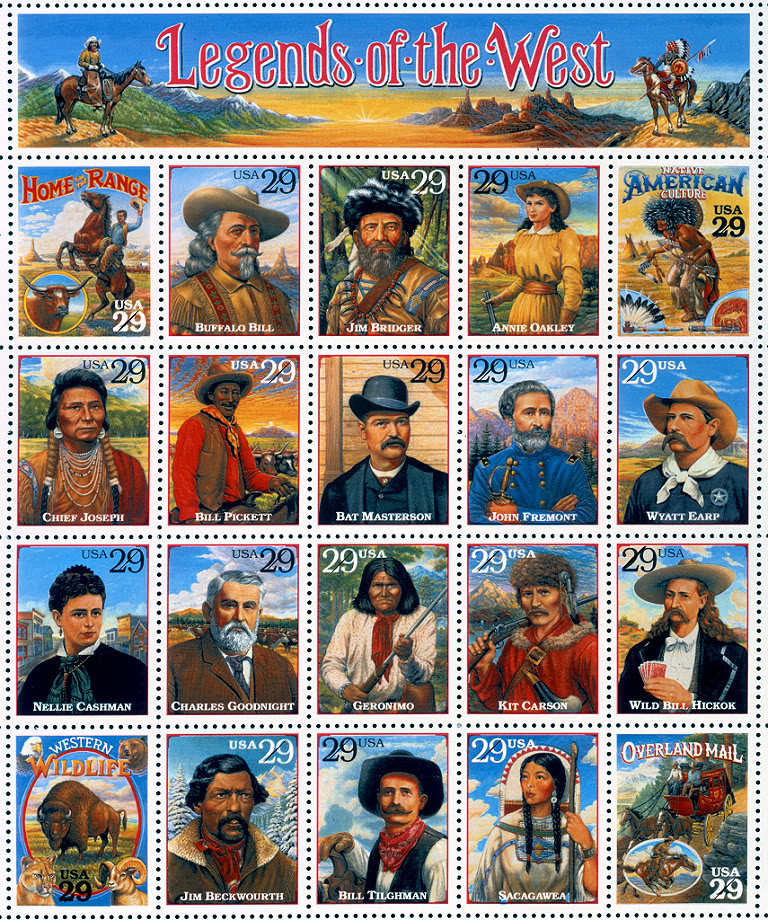

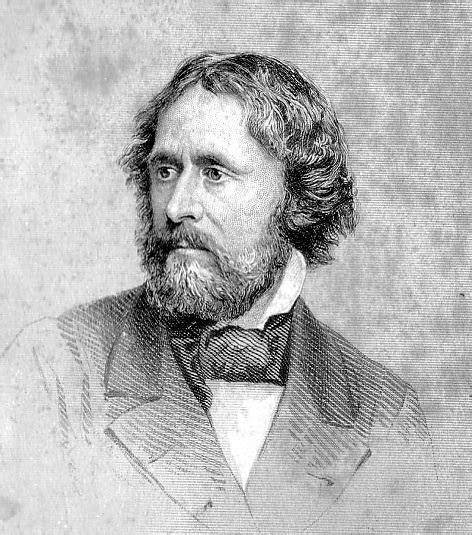

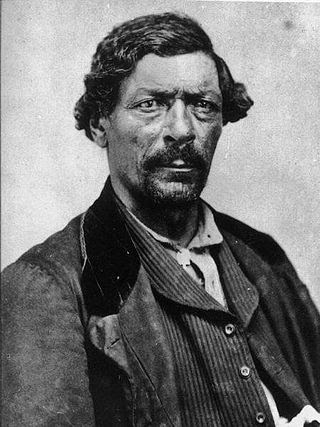

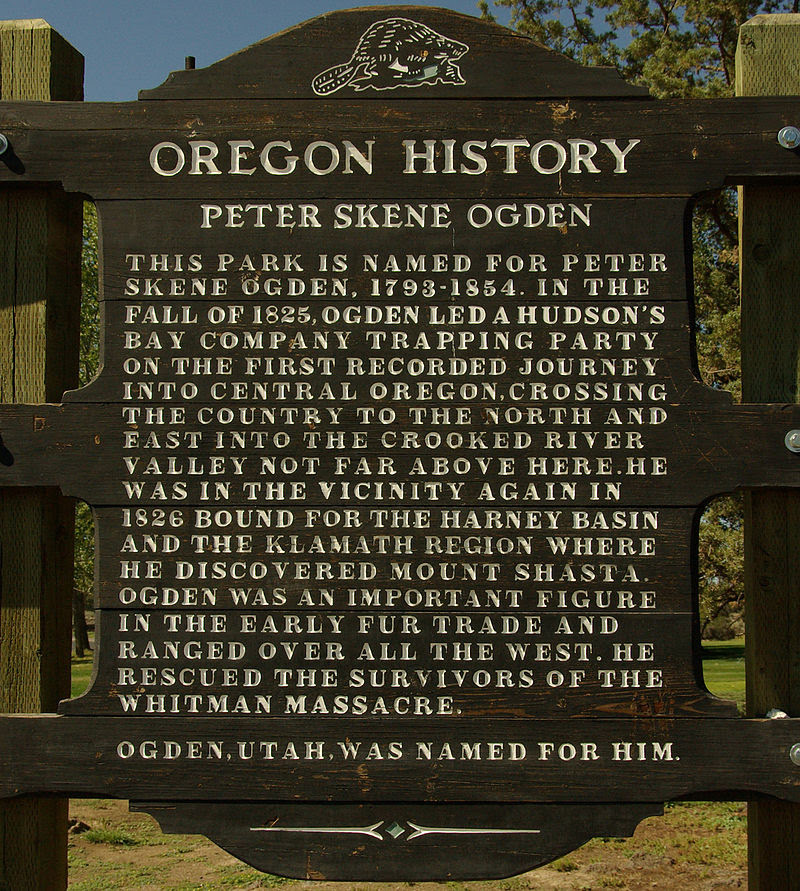

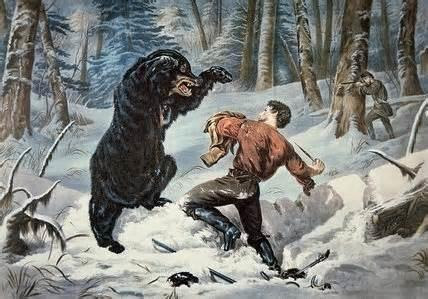

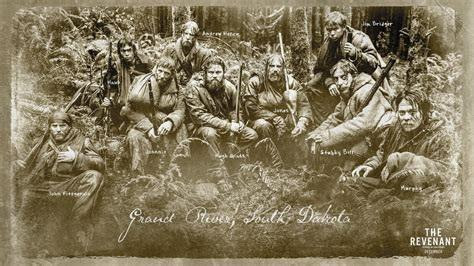

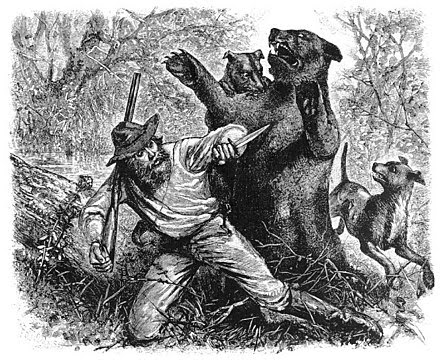

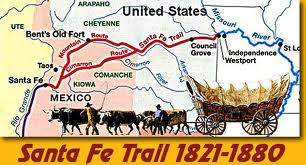

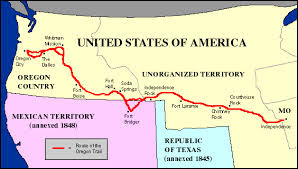

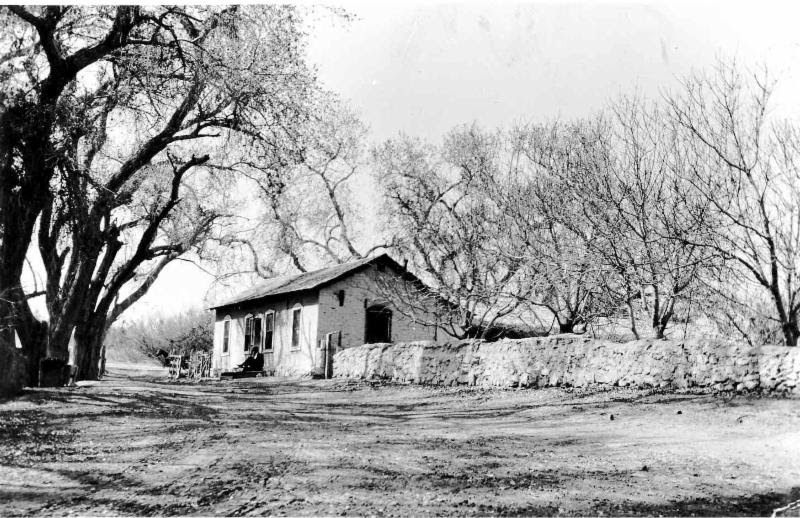

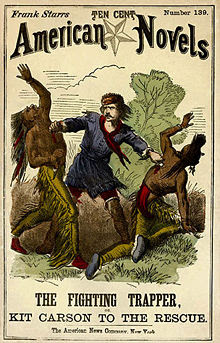

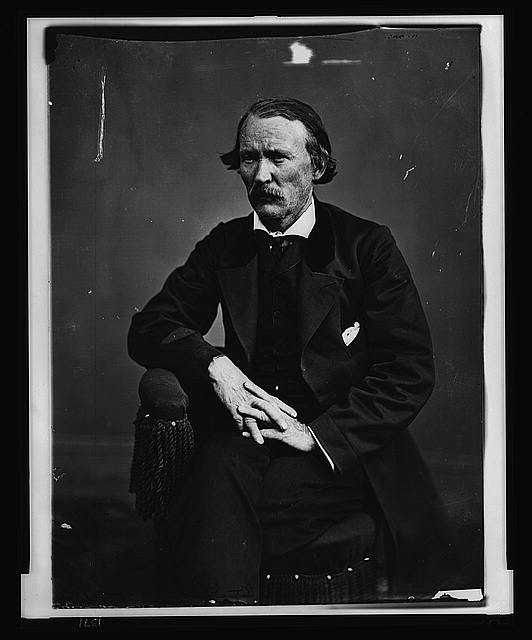

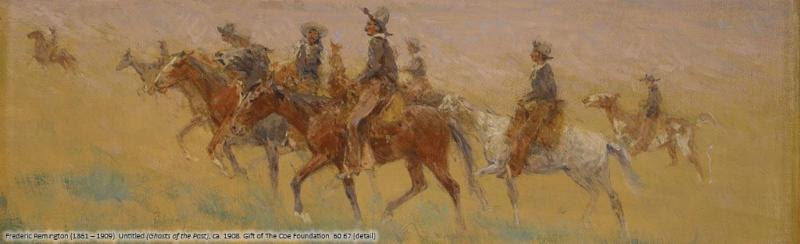

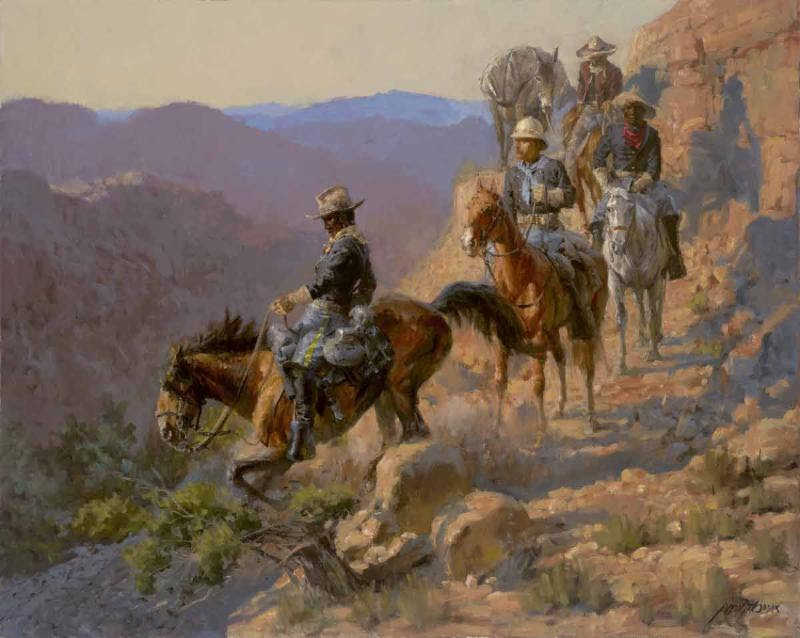

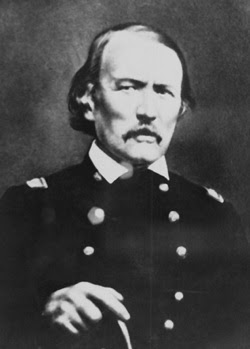

Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, & the Mountain Men

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disabled veteran needs help replacing bridge that often floods, trapping him at home

Disabled veteran needs help replacing bridge that often floods, trapping him at home Pastor Daniel Ulysses endorses Sea Quest Kids and WE THE KIDS

Pastor Daniel Ulysses endorses Sea Quest Kids and WE THE KIDSRecent Posts

The Gettysburg Address-We The Kids Friendly Version

A long time ago—87 years ago, to be exact—our Founding Fathers created a new country right here in America. They believed in freedom and that all people are created equal. Now, we are in the […]

WTK Reporter Libby interviewed Professor Jonathan W White, PhD

Jonathan W. White is professor of American Studies at Christopher Newport University. He is author or editor of 19 books and more than 100 articles, essays and reviews about Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, slavery […]

“We cannot walk alone” Rev. M.L. King, Jr., Baptist Pastor – American Minute with Bill Federer

American Minute with Bill Federer

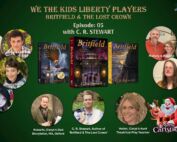

Episode 05: WTK Liberty Players and ‘The Britfield & The Lost Crown’ Radio Show | C. R. Stewart

Experience the captivating ‘Britfield and the Lost Crown’ radio show, presented by We The Kids Liberty Players. Explore themes of family, courage, and history in an engaging storytelling adventure featuring guest appearances by historical figures […]

Episode 04: WTK Liberty Players and ‘The Britfield & The Lost Crown’ Radio Show | Charlotte Bronte

Experience the captivating ‘Britfield and the Lost Crown’ radio show, presented by We The Kids Liberty Players. Explore themes of family, courage, and history in an engaging storytelling adventure featuring guest appearances by historical figures […]

WeTheKids S2E3-Signers of the Declaration of Independence & Interview with Abigail Adams

We are excited to highlight a truly captivating episode from WFYL 1180 AM’s airwaves. The radio show “Signers of the Declaration of Independence of USA & Interview with Abigail Adams” offers listeners a unique blend […]